story

Beyond Questioning Strategies

Blog

lesson design. Joaquín was a bright student with a great sense of humor and a strong creative streak, so, I could have anticipated what he would do, but I did not. That day, the class was ideal; students were quietly completing writing exercises in their workbooks. You could hear a pin drop.

Share

Since the time Joaquín was sitting in my Spanish 3 class, student engagement has been a key guidepost for me in lesson design. Joaquín was a bright student with a great sense of humor and a strong creative streak, so, I could have anticipated what he would do, but I did not. That day, the class was ideal; students were quietly completing writing exercises in their workbooks. You could hear a pin drop. A dream class, right?

Suddenly, Joaquín put his pencil down, stood up, and walked to the window. He opened the window, stuck his head out, and screamed. Then, he closed the window, walked back to his seat, and sat down. And stared me down. The class and I stared back with our mouths opened. The bell rang and I came to, closed my mouth, and vowed to change the way I teach. Obviously, workbook exercises were not cutting it with student engagement, or with helping students acquire the language.

We now know that communicative ability cannot be drilled, and as evidenced by Joaquín, drills are stifling. Bill VanPatten, a current researcher in second language acquisition, writes that, “[Communicative ability] cannot be practiced in the traditional sense of practice. Communicative ability develops because we find ourselves in communicative contexts.” As a result, world language teachers are moving to proficiency-driven classrooms in which students are immersed in the target language, engaging in real-world tasks, using language to explore content in intercultural contexts, and showing what they know and can do via performance assessments.

Fortunately, authentic resources, the springboard for content and language acquisition, are readily available. Because of the Internet, all types of print and audiovisual materials are at our fingertips now more than ever before. But are students truly accessing the authentic resources? How do your students move from reading or listening to a resource to talking or writing about the content it presents? Often, we have students answer a series of questions to gauge their comprehension of the material. Proper questioning strategies can be a powerful learning tool, as seen in TCI’s Visual Discovery strategy from their History Alive! curricula. In Visual Discovery, students view a photo, infographic, or video and respond to a line of questioning in progressive order from the factual to the interpretive, and finally to the hypothetical.

While questioning engages students in higher order thinking and creativity, too much of a good thing can get old and result in disengagement, so let’s take a look at some of the other ways learners can show their comprehension and expand on what they have learned. In the first blog post in this 3-part series, we examined pre-reading/listening/viewing strategies. Next week, we will examine what students can do post-reading/listening/viewing to get the most from authentic resources. Today though, we will focus on ways to help students more fully understand an authentic resource during their engagement with it.

During-reading, listening, and viewing strategies help students make connections, monitor their understanding, generate questions, and stay focused. They make what used to be considered a passive task into an active, and even interactive, one.

To help you get started, I have included 5 strategies to engage your students during reading, listening, and viewing:

Have students highlight, circle, or underline key vocabulary, language structures, or content to identify the main idea and supporting details of a print text. The opening paragraph of the short story, Una carta a Dios by novelist of the Mexican Revolution Gregorio López y Fuentes, lends itself to this strategy on several levels: geographic terms, the imperfect tense, and cultural references.

La casa... única en todo el valle... estaba en lo alto de un cerro bajo. Desde allí se veían el río y, junto al corral, el campo de maíz maduro con las flores del frijol que siempre prometían una buena cosecha. Lo único que necesitaba la tierra era una lluvia o, a lo menos un fuerte aguacero. Durante la mañana, Lencho... que conocía muy bien el campo... no había hecho más que examinar el cielo hacia el noreste. —Ahora sí que viene el agua, vieja. Y la vieja, que preparaba la comida, le respondió: —Dios lo quiera.

When the material is in audio or video format, provide students with a word bank or a word cloud, and have them highlight the words they hear.

Students love being asked their opinion, so capitalize on that as they are reading a text. Have them use symbols to express their reactions to what they read, such as:

The same can be done with a video or audio, but students note the time marker next to the symbol.

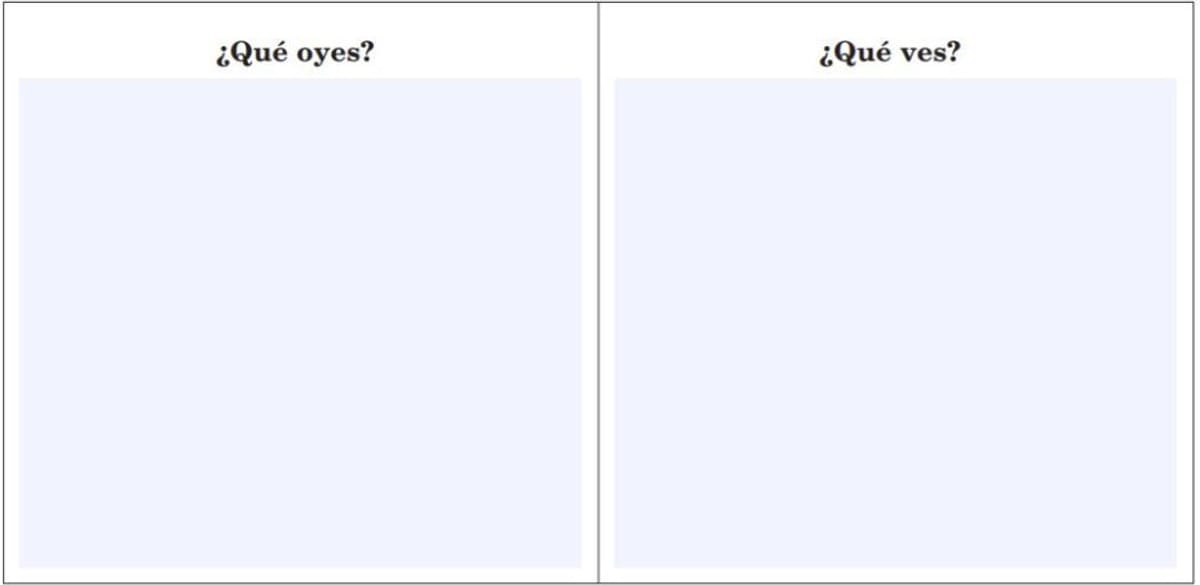

Graphic organizers are a great tool to help students take notes, especially when students are faced with interpreting complex texts or audio. The notes give students a reading guide to use as they navigate through difficult text, and they act as a model of how students should organize their ideas as they are reading, listening, or viewing. They can be simple and more open-ended like this example, in which students first note what they see in the video. The second and third times they watch the video, students add what they hear in the second column.

Yes. I am suggesting questions, even though we’re looking at strategies that go beyond questioning. But in this case, students create the questions. Take this example:

You’re traveling in Puerto Rico or Canada with your pet when he gets sick. You need to call an animal hospital and set up an appointment to have him seen by a veterinarian. Scan the ad you find in a magazine (or listen to the TV commercial) and write down questions you will need to ask.

A great way for students to show they understand a text or an audio is to have them draw it, write or speak map directions, or create instructions on how to make something. It is important to make sure the resource contains imagery that facilitates this type of strategy, though. Alternatively, you could have students select clipart or photos to represent what they read or hear. Make sure the resource contains imagery that facilitates this type of strategy. The story, Una carta a Dios, that we referenced at the beginning works well for this. Written or audio directions from place to place or instructions on how to make something also work well. This poem by Gloria Fuentes, El río recién nacido, also lends itself to illustrations.

El poeta de ciudad

Se va al campo a respirar.

Montado en su bicicleta

Se va a la montaña el poeta.

El río recién nacido,un hilo de agua entre las piedras,

míralo, no te lo pierdas.

Give one or more of these strategies a try with your students. Engaging your students by having them interact with the material while they are ingesting it takes them further than just having them answer comprehension questions afterward. By conducting “during” activities, students will develop a much richer sense of what they are reading, listening to, or viewing, and it will help prevent your “Joaquín” from screaming out of the classroom window.

In the final blog post of this series, we will discuss follow-up strategies and activities that provide students with opportunities to talk and write about what they have learned, so stay tuned !

_____________________

Van Patten, B. (2014) Creating Comprehensible Input and Output: Fundamental Considerations in Language Learning (pp. 24-26). ACTFL, The Language Educator, Oct/Nov 2014.

Betancourt, F. (2015, October 20). COCTEL DE FRUTAS Delicioso [Video]. Youtube.

story

Beyond Questioning Strategies

story

Authentic Resources

story

Classroom Strategies